The Man Who Loves Grass

by Edie Clark

Photographs by William Huber

Copyright © 1991 Yankee Publishing Inc.

Reproduced with permission.

Melvin Longley is not a botanist or an herbalist or a feed-grain specialist. But the Smithsonian Institution invited him to Washington just to talk about his favorite subject.

IN THE DISTANCE THE red tractor moves soundlessly across the hayfield. It is 11 o’clock on a Tuesday morning in July in Shirley Center, Massachusetts. The thermometer by the kitchen window of the Longleys’ farmhouse reads 86. The sun is hot and round, rising high in the sky. The tractor comes close enough across the grassland to hear, until the engine’s noise takes over the landscape and Melvin Longley brings it to rest between the redbrick house and the barn. He presses his forefinger on the kill switch and silences the chum-chum-chum-chum of the Farmall. With one hand on the big round fender he eases himself down onto the grass, now shorn close by the cutter bar. He has been haying. He does it now piecemeal, a little at a time, not like he used to, sweeping the whole wide field in an evening. He’s older now and his legs give out on him pretty easily. He gave up the cows almost 20 years ago. But the haying, the mowing of the grasses on this nearly 100 acres of grass and swampland, he won’t give that up. Grass is what holds the magic for him.

Say the word “grass” to Melvin and a kingdom unfolds for him, one that includes as rich a cast of characters as any Hollywood production. In his time on this earth, which is now 71 years and all of it spent in this town, he has come to be known as an expert on grass. If there can be such a thing. He knows grasses, as a farmer should, but he is not a botanist nor is he an herbalist or a feed-grain specialist. The grasses he loves and about which he knows so much are the weeds, the tiny flowers of the field and the pesky harbingers of hay fever. He is simply a man who loves the grasses as the bird-watcher loves the birds. In 1988 the Smithsonian Institution invited him to come down to Washington to be part of its Festival of American Folklife, to show off what he knows about grass and other things of country life, about which he knows as much as anyone, it seems.

He went down with Louise, his wife of 51 years. Into an Allied Moving Van, sent to the family farmhouse on Whitney Road, moving men loaded about 800 pounds of Longley treasures — including tools and a workbench, flails, ox yokes, brooms, and bundles and bundles of grasses. And then he and Louise flew down together with just a borrowed suitcase packed with their clothes. “Louise and I had never been off the farm for one week, to say nothing of two weeks,” he said. For two weeks they held forth in a booth in a pavilion, talking about grass and crafting the rustic hearthbrooms (Melvin is locally famous for these) whittled in one piece from the branches of a witch hazel tree. For two weeks Melvin Longley was more or less on display, dispersing the lessons of a lifetime to the crowds that gathered, coming in from under the shadow of the Washington Monument, curious, interested, amazed by this slight, somewhat bent man who, with his sideburns and carefully combed hair, his Western shirts with snap buttons, looks more like a cowboy than a Yankee farmer.

Melvin remembers his time in Washington with an amused smile. It came and went, a little chapter in his life that Louise tucked into his scrapbook with the other tributes from the local papers — when he stopped milking cows on the homestead (the first time there had been no cows in the Longleys’ barn since 1643), the write-ups on the nature displays he used to put up at the elementary school when he was head custodian, and the time the town of Shirley Center declared a day in September to be “Melvin P. Longley Day” and had lemonade and ceremonies in his honor.

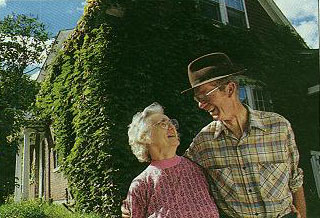

Melvin brushes the hay chaff from his work pants and goes through the screen door into his kitchen. Inside his house, which is close by the road and covered with the fullness of ivy vines, Melvin can point to the room where he was born. He and Louise sit at a table he made of pine from his woods. Nearby is the bed he made from the wood of the cherry tree that he and his father cut at the edge of the hayfield. It’s a good bed for him, he says, because it’s more than six feet long. He can stretch right out in it.

Melvin found out most of what he knows about grasses by reading. He has Parkinson’s disease, which makes it hard for him to move around as much as he used to, so he reads a lot. “Now, when I’m resting my legs, which I have to do quite often, I have plenty of time for reading,” he says. “Lots of times I wake up about half past four, so I get up, have a dish of cornflakes, and read for a while. Then I go back to bed and I can get to sleep.”

It was from a U.S. Department of Agriculture yearbook that he first began to learn about the rich and well-populated world of grasses. “I’ve always been interested in grasses,” he says, seated at his table. “If you stop and look, they really are flowers. Although the blossoms are minute, they are beautiful — and so different. The grasses that we grow commercially are only a very tiny proportion of the grasses that are self-seeded and grow here naturally. Some of them have uses and some of them have no use that I have found out. The only difference between a vegetable and a weed is that they haven’t discovered what to do with the weeds. If we got really hungry, there are a lot of things growing out there that we could eat.”

On his land Melvin says he has identified 60 or 70 varieties of grass and 58 different kinds of trees. “Grasses and trees fascinate me, even so far as in the wintertime when I’m putting a stick of wood into the stove, I really can’t throw it in without identifying it first. If I don’t quite know, I stick in a different piece and wait and think about that one.”

share a laugh outside their ivy-covered house.

Melvin gets up and goes into the pantry. He returns with a saucer filled partway with water. He holds out his hand to show me the seeds in his palm. “Sweet vernal seeds,” he says and then empties them into the water. Like sleeping animals coming to life, the seeds spin in slow circles. They jump and twist in the pool. Louise watches this little sideshow and laughs. She has seen it countless times, but her eyes sparkle to see it anew. She has learned a lot from Melvin. “Things that you would never dream of, you know?” she says.

“I have seen them jump out of a dish,” he says. He is enjoying this, the way Louise is. “They’re planting themselves,” he explains. “Each seed has two horns, hairlike things that stick out, and water twists one one way and one the other and they work against each other to make the seed roll over. In a year’s time, with sunshine and dry weather, they will twist themselves an inch into sandy soil.” And then come not in such a spectacular way,” he says. “I tell the kids how many ways there are for seeds to plant themselves. Like water lilies — the seeds form like a little boat, and after they drop off the plant, it takes three days for that little boat to dissolve so they sink. By the time three days have passed, they’re far enough away from the mother plant to have a place of their own.”

(click on this picture for a much-larger annotated version)

Like so much else that he knows, he read this in a book. Then he went out and looked for some sweet vernal. There is sweet vernal everywhere in New England. “People say, where do you find it?” he says. “Well, just look down.”

If you go to visit Melvin Longley, he’ll want to show you the grasses, but first he’ll want to show you the church. Somehow it is that the town and the land there in Shirley Center are woven in and around the Longleys like a fine tapestry, bright with the colors of their lives and the lives of their ancestors. Melvin says that his grandchildren are the 12th generation to live on that land there on Whitney Road. The front rooms and the hallways of his house are wainscoted with wood from the old pews and doors taken from the First Parish Meeting House (which Melvin calls “the church”) when it was renovated and “modernized” in the late 1800s. He and his family before him have cared for that church down through the ages.

“And so I began,” he says of his four-year project to single-handedly restore the interior of the church. There were two layers of paper to be taken off. He left the paper, where it was still decent, and razored off the rest. And then he duplicated the yards of molding paper that needed to be replaced, painting in the 29 stripes by hand, using the colors of blue and gray and brown that he mixed himself to match the old paint.

The ceilings are three stories high. He had to build staging to get up there. “I chased around most of the neighbors at one time or another to come give me a hand to move my staging.”

Mostly, this was a labor of love. “At first, I was charging two dollars and a quarter an hour. Then I saw that it was going to be such a big project that I quit sending bills.”

Not long ago, the spire needed repair. Melvin had an idea. Hallmark once used a picture of this church on a Christmas card. Melvin sat down and wrote them a letter. “I used my most persuasive rhetoric in the hopes they would make a contribution to the restoration of the spire.” His efforts were unsuccessful. But the spire was repaired, thanks largely to Melvin Longley.

“Do you want to go way up?” he asks. The Meeting House tower is a challenge, worth it for the view. We clump up the narrow winding stairs that get narrower and steeper with each turn. Finally, an ascent like a ladder up to a hatch in the roof. My resolve weakens.

“It’s nice, he says, his only encouragement as he reaches the top and pushes out the hatch that lets in a shock of light. He disappears out onto the roof. I continue on up, to the crown of Shirley Center. From there the little village, its common ringed with historic houses, looks like a scene from a picture book. He comes up here quite often. “When I want to took around, ring the bell,” he says. He leans over and begins to rock the enormous bell. It gains momentum in its wooden cradle and then DONG! the sound of the bell pulses out across the common. A dog barks into the summer air.

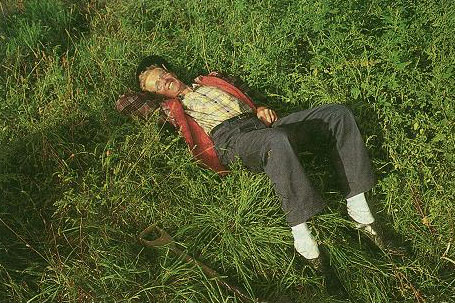

It is getting into the afternoon. There are puffy white clouds skimming the edges of a very blue sky. Melvin says, “That sky tells me I’d better get back to the field.”

WHEN WE GET BACK TO THE HOUSE, though, he decides that the haying can wait. He wants to take me to see the grasses. In his Ford sedan we start off across the flatness of the field. He used to walk out into the fields to collect the grasses.

“Too far for my legs now,” he says. “For years I dreamed of walking to Ohio and stopping to work for a week or two and then moving on.” He laughs mildly. “I’ll never do it.”

We move along, the grasses brushing the underside of the car, a steady stroking sound. At the far side of the field, he stops the car and turns off the engine. “Most years, there’s a lot of nice grains and sedge in here. But there’s also poison ivy so I think you’d better let me go in.” He moves into the depth of the grasses, which move around him in the afternoon breeze like a rising tide. He slides his knife out of his pocket and opens the blade, bends and cuts a stem. It is a long-stemmed grass with several exaggerated tassels at the top. “Fringed sedge,” he says, handing it to me. He points out the triangular stem with his fingernail, which is as thick as a nickel. “The sedges have three-cornered stems. That’s how you can know them,” he says. “Feel the sawtooth on the edge?” It is sharp, a tiny saw. “That keeps insects from moving up and down the stems.” He moves back into the grass, cutting a stem here and there as he wades along and then returns, handing me a bouquet of the grasses.

The field we are driving across is mostly timothy, but some clover is coming in. Fort Devens, a big military training base, is nearby, and paratroopers use this field for drills. He cuts this part first so they can use it. They put an orange arrow into the middle and try to land as close to the arrow as they can. One jumper landed in the tree across the road a white ago and had to be rescued by the town firemen. Melvin likes this story, and he tells it to me in detail as he pulls the car to a stop again and gets out.

He takes me down to show me a patch of what he calls saw grass — is it useful for anything? “Nope, not that we know of.” We walk through the sharp blades. He points out another called blue joint.

Horse mint.

He shows me fox sedge — the top is like a foxtail.

Hidden in the grass is a crowd of forget-me-nots. He points them out. And then wild iris, the blue blossoms withered into papery skins.

The earth we are walking on is marshy, and it looks something like a salt marsh: wide and open, veined with streams. “Back when they mowed these places with scythes, they’d wait till late in the season when it was dry. My father said that he and his father used to pole hay out of there, carry it out between two poles. Because it was so wet, you couldn’t get a wagon in there. Some of the farmers used to use brackets on their horses, something like snowshoes. They’ve lost horses in the mud, you know, had to kill them right there.”

All around us are the mechanical sounds of grasshoppers and crickets, spaced with the cheerful hoorah! of the redwing blackbird. Overhead, the martial rhythm of a chopper blade thrums closer and closer — a reminder of the other world.

He bends to point to sweet vernal. He doesn’t say the name, but looks at me to see if I recall this morning’s lesson. I do. “Most everywhere you go you see the sweet vernal,” he says. “And quite a lot of black snakes,” he calls back as he moves back toward the car. He has gathered a bundle of grasses and bulrushes that he cradles into the back seat. He dries the grasses he collects on a screen in the old milking parlor of his barn. He ties them and tags them for exhibit. And sometimes he takes vases of an assortment of grasses over to the church for reserve, in case they don’t have flowers for the altar.

“I want to show you Paradise,” he says. I follow Melvin through tall grasses to the woods. He steps over barbed wire and goes down into a vale. Tall hemlocks guard a deep rock crevice. Their height gives the place a sacred feeling. The river sluices down through a V of solid ledge, smooth like the sides of a porcelain basin.

It is a place the Longleys call Paradise, Melvin tells me. For a lot more than 100 years, they’ve been calling it that. The waterway is Paradise Brook. On the map it is called Spruce Swamp Brook. On the map what the Longleys call Paradise is Spruce Swamp. It’s just as well. If they called it Paradise on the map, more people would come. Enough come as it is.

Back in the car, he starts the engine and pulls it into gear. We move again out onto the prairie. “I like the meadow sweet and the hardhack, the steeple bush.” Alongside the car is what he calls buckthorn. He slows. “They used to use that to make yellow dye,” he says. And he identifies for me a familiar grass: a low-growing grass with a tint of red. A crop of it can give the roadside a reddish hue. I’ve seen it all my life but never knew the name. Red top.

There is also yarrow and milkweed and goldenrod. He pauses over a waving stem. Sometimes now, he forgets the names of things, has to stop and think. At last, the words come. Balm of Gilead.

There are others, so many others. This is just a scanning of the commonplace. Yard rush. Rabbit’s foot sedge. Canada rush. Yellow foxtail. Bog rush. Red dock. He stops to tell me this: Redwing blackbirds tie two or three stalks of red dock together to make their nests. Purple vetch. Tussock.

Louise walks out into the field. She likes the grasses too and knows some of them by name now.

“I want to find the heavy-fruited English blue grass for her,” he says to Louise. “I know there is some in here.”

Her eyes begin to sweep the landscape. “I’d recognize it if I saw it,” she says.

Melvin and Louise roam through the yellows and greens and lavenders of the mid-summer meadow. “I’ve got it,” he says, and they respond with muted cries of pleasure. He moves toward it and cuts a stem of it, holds it up, the showy seed pods waving like small flags.

Reproduced from Edie Clark, “The Man Who Loves Grass”, Yankee Magazine, Vol. 55, No. 8 (August 1991), pp. 79-83, 126-129.

Melvin Longley passed away on November 24, 1997.